First published in http://muchadoabtshakespeare.blogspot.com/2015/ on Monday, 21 December 2015

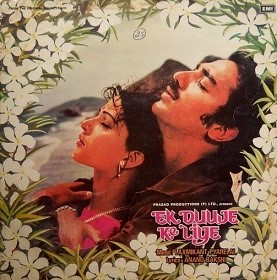

The first reworking of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet on screen in Bollywood was undertaken in the form of Ek Duuje Ke Liye, which was the Hindi remake of the Telegu Maro Charitra (1978). Both films had south Indian superstar Kamal Hasan playing the lead role. The film was a box office success, earning a total of Rs. 100 million in receipts, and winning a National Film Award and three Filmfare awards. This was the first Hindi film post-independence in a modern setting to quote and reference Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Ek Duuje Ke Liye also avoids the usual dichotomies that are available within the Indian context such as religion or financial and/or social status and locates Romeo and Juliet within an issue of contention that is rarely addressed on film – the differences between North Indian and South Indian language and culture.

The opening sequence of the film depicts waves crashing against rocks and the empty spaces in a dilapidated temple on top of a mountain. The camera focuses on the graffitied walls, reminiscent of West Side Story, where Sapna and Vasu’s names have been inscribed repeatedly, while we hear the lovers talk off-screen about how their unfulfilled love will become legend for future generations. The sense of tragic inevitability, that is so crucial to an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet but unfamiliar to Indian audiences, is subtly woven into the fabric of a seemingly familiar love story. The setting of the lovers’ meeting place in Dona Paola beach, for instance, hints at the tragic fate of the lovers. The place is named after Dona Paula de Menezes, the daughter of a viceroy, who committed suicide when her father refused to marry her to a local fisherman, Gaspar Dias, whom she loved, and the location is a well-known suicide point for lovers. There is also a reference to a well-known Bollywood celluloid tragic lover – Jai from Sholay (1975) – when Vasu is depicted playing the mouth organ and riding a bike in the scenes where he is wooing Sapna. The lurking presence of a sexual aggressor who has his sights set on Sapna, evoking Samson’s threat of violence towards Montague women (‘women, being the weaker vessels, are ever thrust to the wall’ 1.1.15) and Maria’s assault by the Jets in West Side Story, adds a further sense of disquiet to what would otherwise be a traditional Bollywood love story. This threat of violence against women is incorporated later in Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak as well when Rashmi is stalked by a group of would-be aggressors. Towards the end of Ek Duuje Ke Liye, when it seems that the lovers may achieve their happy ending despite all odds, Chakravarty/Paris reminds Sapna that God is always unfair to true lovers and the audience is once again cautioned against believing in a traditional happy ending for the lovers who have suffered so much in trying to be with each other. Thus, the sense of tragic inevitability of the play is infused in the film in a more understated manner than merely positioning the lovers within the context of insurmountable cultural differences.

The film is particularly remembered for the lovers’ suicide at the end, There were several reports of lovers committing suicides after the release of Ek Duuje Ke Liye; the director was called in several times by authorities to appeal to young couples not to take their own lives. The growing incidence of suicides forced the director to modify the ending but the change was instantly rejected by the viewers, who stuck to their demand for the original climax. The ending of Ek Duuje Ke Liye has particularly influenced more recent adaptations and appropriations of Romeo and Juliet in Bollywood; Ishaqzaadein (2012) and Ram Leela (2013) for instance, both end with the lovers dying at their own hands.

The play itself is quoted several times in the film. Romeo and Juliet is directly referenced in the first instance when Sapna asks for Professor Munshiram’s notes on Romeo and Juliet at a book store she frequently visits. Then, just after the sequence where we see Sapna and Vasu falling in love intercut with scenes of their parents fighting, Sapna reads out: ‘What’s in a name? That which we call a rose/ By any other word would smell as sweet’(2.2.43). This is a theme central to this film which deals with barriers of language and culture and about personal identity. The repetitive scenes where we see the names of the lovers inscribed on walls, in the sand, and in letters, highlights the preoccupation that this film has with the concept of names as being part of a person’s identity. The sequence that any audience familiar with the play would find most faithfully reflected in the film, however, is the one after Vasu is banished. His anguished cry: ‘Why should I banished from this place?…Is sheher mein tumhe janne wale, nahin janne wale, janwar, panchhi, peddh, paude, yahan tak ki choti si choti chinti bhi dekh sakegi. Sirf main nahin dekh sakta?’ (Everyone in this town, people who know you, people who don’t know you, animals, birds, trees, plants, even the tiniest of ants will be able to see you. Why should I be the only one not able to see you?) is a literal translation of Romeo’s protest in the third act of the play: ‘Heaven is here/Where Juliet lives, and every cat and dog/ And little mouse, every unworthy thing,/ Live here in heaven and may look on her,/ But Romeo may not.’ (3.3.29). This is also, conversely, the point in the film where the screenplay deviates from the play text and other locally relevant issues begin to inform the film, such as cultural prejudices that prevail in India. Nevertheless, there are several moments in the film even after this point, when other themes of the play are briefly cited, for instance, the eternal fight between age and youth: ‘Budhape aur jawani ki sangram’ or the equation of love with madness: ‘Love is…a madness most discreet’. (1.1.190)

Ek Duuje Ke Liye begins as a tragi-comedy but devolves into a melodramatic social drama because of the several digressions from the play text and the inclusion of prevalent Bollywood formulaic episodes. Sapna and Vasu’s love is frequently shown to be self-destructive, for instance, when Sapna tells Vasu to jump into the sea to prove his love despite not knowing how to swim or when Sapna cuts herself by gripping a conch shell too hard in an effort not to go to Vasu and break the terms of the contract they have signed to stay away from each other for a year to prove that their love is not merely lust. These scenes seem to lend credence to the doubts that the parents have about their being mature enough to understand what love and marriage entails: ‘Is umar mein pyaar kya hain? Vaasna’ [At this age, what is love? Lust]. Sapna at one point reverts to typical Bollywood heroines by rejecting Vasu for stealing a kiss. Consequently though, like Juliet, and unlike female protagonists in Bollywood at the time, she initiates physical contact with Vasu several times, which renders the formulaic ‘modesty of a woman’ scene pointless. There is also a sequence in the film when Vasu’s love falters and he prepares to marry Sandhya when he is misinformed that Sapna’s wedding to Chakravarti has been finalised. This digression essentially dilutes the intensity of their love and they lose their way as protagonists of a legendary story of love. The plot twist in the end that results in their death also seems somewhat contrived and complicates a reading of this film as being an adaptation of Romeo and Juliet. When Vasu and Sapna fulfil the terms of their contract and finally prepare to meet each other, Sapna is raped by her stalker and Vasu is attacked by assassins on the behest of Sandhya’s brother at the abandoned temple which used to be their meeting place; they ultimately find their happy ending by jumping into the sea together. Their suicide somewhat obfuscates the sense of tragedy that is associated with the deaths of Romeo and Juliet as they essentially become agents of their own destiny. Moreover, neither do their deaths bring about a reconciliation between the families, nor any change in society at large. At the end we are not left with a sense of the futility of hate so much as the impetuosity of love.

Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that in Ek Duuje Ke Liye we find the first attempt at adapting and translocating Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet in mainstream film in Bollywood and it’s influence on adaptations after the 80s is unmistakeable. Here’s a link to the film on Youtube: https://youtu.be/xFAhIrZY5Sc