First published at http://muchadoabtshakespeare.blogspot.com/2015/ on Thursday, 3 December 2015

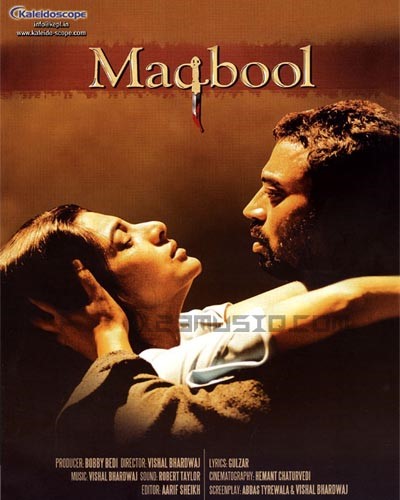

[Was it all a mistake Miyan? Everything? Our love was pure though, wasn’t it Miyan? Was it pure, our love?]‘Kya sab kuch galat tha Miyan? Sab kuch? Hamara ishq to paak tha na Miyan? Paak tha na hamara ishq?’

– Maqbool (2004)

Macbeth, as a story of ambition, treachery and violence seemed tailor-made for the Mumbai Noir genre in Bollywood already made popular with movies like Agneepath (1990), Satya (1998), Vaastav (1999) and Company (2002) which were also big box office successes. As a cultural transposition, Maqbool is largely faithful to Shakespeare’s plotline and characters. Mumbai functions as a kingdom in miniature, with Bollywood itself as one its holdings. The central players- Jehangir/Duncan and his henchman Maqbool/Macbeth – are the local manifestations of royalty. Jehangir is described as the ‘Messiah of the minorities’, a title which establishes the Mumbai mobster as a type of quasi-divine leader. Instead of Donaldbain and Malcolm, however, Jehangir here has a daughter, Sameera who is in love with Guddu/Fleance. Guddu is no hard hearted killer like Maqbool, as is made apparent by his saving Boti/Macduff’s life early in the movie. Guddu/Fleance is developed in detail as a character- much like the 1955 Ken Hughes directed Joe Macbeth’s Lennie/Fleance- because we are given an indication at the beginning of the movie that he will be the antidote to Maqbool. Boti/Macduff, on the other hand, is not as strong a character in the movie but, faithful to Shakespeare’s script, later in the film he flees to Guddu leaving his wife and child behind and in the final sequence of the film he is the one who kills Maqbool.

The most critical change that has been made to the play script for the purposes of relocating it to the Mumbai underworld is the portrayal of Nimmi/Lady Macbeth as Jehangir’s mistress and the object of Maqbool’s desires and ambitions. ‘Macbeth killed for the crown,’ says Abbas Tyrewala, co-writer of Maqbool. ‘A position in the underworld is not as big as the crown. So we make Lady Macbeth the crown.’ Nimmi, therefore, is a reworking of Lady Macbeth’s character, role and motivation in Macbeth. As Amrita Sen points out, Nimmi is a powerful blend of the Shakespearean and Bollywood influences on Maqbool. Unlike Lady Macbeth, ambition alone does not drive Nimmi. Jehangir’s mistress is similar to the fallen women who emerge as love interests of rising gang lords in films such as Dayavan (1988) or Vaastav (1999). Nimmi, unlike the female leads of these popular gangster films, is not a common prostitute, but she certainly shares their desperation and marginalization. For Nimmi, murdering Jehangir amounts to more than mere ambition. Getting Jehangir out of the way translates into survival, a shot at a life with the man she loves – Maqbool. Unlike the usual gangster moll forced into prostitution in movies like Chandni Bar (2001) or Vaastav, as is the Bollywood convention for primary female protagonists, Nimmi, however, seems to have chosen to become Jehangir’s mistress out of free will as a means of becoming a heroine in Bollywood; this is hinted at in the scene when she wants to visit the dargah (mosque) towards the beginning of the movie, and later when she forces Maqbool to choose between her and Jehangir.

The greatest influence on the portrayal of Nimmi, though, is Asaji from Throne of Blood (1957) directed by Akira Kurosawa and set in feudal Japan. The woman who coldly and calculatingly manoeuvres her husband by planting insecurities in his head and forcing him to ‘take the nearest way’ in order to fulfil his destiny finds a recognisable echo in Nimmi. Asaji seems absolutely impervious to the consequences of doing away with people who are in her husband’s way. She makes him believe that Miki will tell Lord Tsuzuki about the witch’s predictions and use it to his own advantage by making him think that Washizu is a traitor and when Washizu decides to name Miki’s son his heir in order to keep Miki loyal, she taunts him with the idea that he has sinned for the benefit of Miki’s future generations. Lady Macbeth states what she has to in order to give courage to her husband, but she never plants insecurities in his head, nor does she taunt him except when he displays fear. She firmly believes that her husband must take matters into his own hands in order to achieve his rightful destiny, though why she thinks he needs to take ‘the nearest way’ is never quite explained.

Nimmi similarly uses Guddu/Fleance to make Maqbool insecure and she uses every chance she gets to manipulate situations so that Maqbool must face his feelings for her. Most of her manipulations, such as when she steps on a sharp object so that Maqbool is forced to hold her hand in order to support her, or when she holds a gun to him and tells him to call her ‘Meri Jaan’ [my love] seem reminiscent of Lady Kaede’s manipulations from Ran (1985) and some scenes such as when she holds the jug of water out of Maqbool’s reach when he comes to fetch it for Jehangir who is choking on his food, or her rubbing her relationship with Jehangir in Maqbool’s face at the end of the dargah sequence seem intentionally cruel. She ruthlessly uses Maqbool to get what she wants – a life with the man she loves.

The child mentioned by Lady Macbeth, and carried and subsequently lost by Asaji also appears in Maqbool. Nimmi’s descent into madness is triggered by her pregnancy, however; Asaji’s madness is triggered by miscarrying. This is in keeping once again with the Bollywood tradition of sons avenging the deaths of their father, the central theme in Agneepath for example. The likeness between Asaji and Nimmi is made most obvious, however, when they deliver the exact same question to their husband/lover on the eve of the murder: “So, have you decided?”

Lady Macbeth is not a black villain like Goneril or Regan. As Hazlitt puts it, ‘Her fault seems to have been an excess of that strong principle of self-interest and family aggrandisement not amenable to the common feelings of compassion and justice, which is so marked a feature in barbarous nations and times’. She also consciously tries to reject her feminine sensibility and adopt a male mentality because she knows that her society equates feminine qualities with weakness. Yet she cannot commit the murder herself because Duncan reminds her of her father, and she needs spirits to fortify herself when she sends her husband in to kill the king. At the end, it is this dichotomy in role and nature, along with her husband’s growing indifference and lack of need of her, which leads to her mental disintegration.

Asaji, on the other hand, is almost portrayed as a counterpart of the witch in Throne of Blood. The whispery quality of her voice, her eerie stillness, the way she continues to plant seeds of doubt in Washizu’s head, all seem an extension of the mind games that the witch played on Washizu and Miki at the beginning of the movie. The scene where she goes to fetch sake for the guards makes this comparison most apparent. She literally ‘disappears’ into the darkness, and then magically seems to reappear with a jug of wine.

Asaji suggests murder in a tone of practicality. Theirs is a society where one must kill or be killed. There is no suggestion that she feels any compassion for the victims nor that she has to suppress her feminity in any way in order to suggest murder. For her it is a simple matter of survival. However, the witch had prophesized that Washizu would be king, but that Miki’s son would succeed. While she took the first part of the prophesy as truth because it suited her ambitions, she ignored the second part. Her disintegration happens when she realises that she has tried and failed to change her destiny.

Nimmi too lives in a society where bloodshed is inevitable. According to Tony Howard, ‘Gang wars provided a modern context for the play’s tribal codes of violence’. The ‘kill or be killed’ ethos of her world is brought to focus right from the start of the movie. She is as Machiavellian as Asaji; it is only her ambition that is different. She too plays on Maqbool’s fear of being supplanted, but the ace up her sleeve is that Maqbool desires her much more than he desires the ‘kingpin’ position. She is the prize, and she knows it. She blatantly uses her feminity, without regret or remorse, to achieve her goals. Once pregnant however, she begins to doubt her justification. The fact that she has murdered the father of her child begins to haunt her. It is not made obvious whether the child is Jehangir’s or Maqbool’s and this makes her descent into madness more poignant. Maqbool always puts her first, however, before everyone, before business (much to the disgust of his associates), before his own safety. He risks his life trying to come back and fetch her before he attempts to flee the country. Nimmi dies seeking assurance that their love was true, that their love was worth this kind of end.

Traditionally, Lady Macbeth is played as the virago or the determined, manipulative wife behind the ambitious yet weak man. ‘Like Macbeth’s evil genius, she hurries him on in the mad career of ambition and cruelty from which nature would have shrunk.’[6] Asaji and Nimmi, though inspired by Lady Macbeth, are characters in their own right and can be viewed as such without any prior knowledge of the original play text. The former behaves almost like a mature advisor to her husband, while the latter is the heroine of a typical love story where obstacles must be crossed in the pursuit of love. Taken out of context, and looking at Maqbool within the background of Bollywood movies, Nimmi and Maqbool may even belong to a world of star-crossed lovers in the tradition of Romeo and Juliet, Shirin and Farhad or Laila and Majnu.

Maqbool is available on Amazon Prime: https://www.amazon.com/Maqbool-Irrfan-Khan/dp/B085RDTZV8